Valley of the Kings

Each tomb reveals fascinating architectural achievements that demonstrate the ancient Egyptians' remarkable engineering skills. Queen Hatshepsut's tomb extends nearly 700 feet from its entrance to the burial chamber, earning distinction as the valley's longest monument. KV5 presents an even more astounding feat—over 120 chambers carved specifically for the sons of Ramesses II, making it the most intricate tomb structure discovered. The valley captured worldwide imagination when Howard Carter uncovered Tutankhamun's pristine tomb in 1922. Yet discoveries continue to emerge from this ancient landscape—archaeologists revealed the 63rd tomb (KV63) in 2006, confirming that countless secrets still await beneath the valley floor.

The Origins and Purpose of the Valley of the Kings

Egypt's burial traditions experienced a dramatic transformation during the New Kingdom period. Centuries of pyramid construction gave way to an entirely different approach around 1539 BCE, when royalty discovered the hidden potential of a secluded desert valley.

Why pharaohs abandoned pyramids for hidden tombs

Security concerns drove this monumental shift from pyramid construction to concealed rock-cut tombs. Pyramids, despite their magnificent scale, had repeatedly fallen prey to determined tomb robbers throughout Egyptian history. Ancient official Ineni documented this new emphasis on secrecy when describing Thutmose I's tomb construction: "I supervised the excavation of the cliff tomb of his majesty alone — no one seeing, no one hearing". Secrecy had clearly become essential to royal burial planning.

Thutmose I (reign 1504-1492 BCE) established the first confirmed royal tomb within the valley, though evidence suggests Amenhotep I might have pioneered this practice. Earlier pharaohs had already begun experimenting with separation—Ahmose I's pyramid at Abydos positioned its burial chamber over half a kilometer from the main structure.

The significance of the Theban Necropolis

The Valley of the Kings nestles within the expansive Theban Necropolis, stretching across the Nile's west bank opposite ancient Thebes (modern-day Luxor). This massive burial complex covers approximately 10 square kilometers, encompassing thousands of tombs, temples, shrines, and specialized workshops.

Thebes' elevation to capital status during the Middle and New Kingdom periods transformed the necropolis into Egypt's premier burial destination. Pharaohs and nobles selected this site for nearly 500 years of continuous use. Ancient Egyptians intentionally chose the western bank because this direction connected with the setting sun, representing death and the soul's journey to the afterlife.

The role of al-Qurn mountain in site selection

Natural geography profoundly influenced the valley's selection as a royal cemetery. A distinctive peak called al-Qurn ("the horn" in Arabic)—known to ancient Egyptians as Ta Dehent ("the peak")—dominates the landscape. This mountain presents an almost perfect pyramid shape when observed from the valley entrance.

Egyptologists widely believe this natural pyramid formation directly influenced the burial ground's selection. Royal tombs positioned beneath this pyramid-like peak allowed pharaohs to maintain symbolic connections with traditional pyramid burials while benefiting from enhanced security. Al-Qurn essentially functioned as a natural monument, eliminating the need for artificial pyramid construction while preserving the profound symbolic meaning these structures held in Egyptian religious concepts of divine ascension and eternal transformation.

The Valley of the Kings served as the primary burial ground for Egyptian pharaohs and nobles during the New Kingdom period (1539-1075 B.C.). It offers invaluable insights into ancient Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife, showcasing elaborate tomb designs, religious symbolism, and artistic achievements of the time.

Tomb Architecture and Evolution Across Dynasties

Royal tomb construction underwent remarkable transformation throughout Egypt's New Kingdom period, each architectural shift reflecting evolving religious concepts and security strategies.

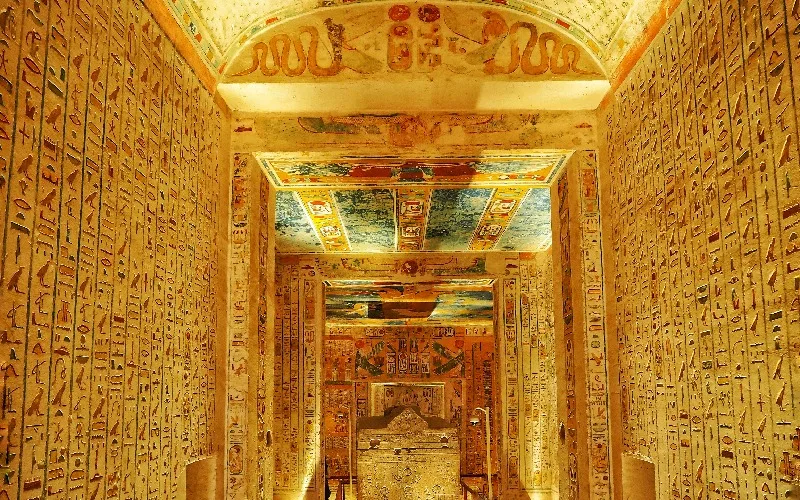

Bent axis vs. straight axis tombs

Early Eighteenth Dynasty tombs exhibited a distinctive "bent axis" configuration, featuring sharp angular turns within passages that led toward burial chambers. This intricate layout deliberately mimicked the sun god Ra's nocturnal voyage through the underworld. Thutmose IV's tomb (KV43) exemplifies this period with its cartouche-shaped (semi-ovoid) burial chamber. Post-Amarna Period construction witnessed gradual straightening of tomb designs, initially adopting "jogged axis" arrangements visible in Horemheb's tomb (KV57). Most Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasty pharaohs ultimately selected "straight axis" configurations, perfectly demonstrated within the tombs of Ramesses III (KV11) and Ramesses IX (KV6).

Use of wells, shafts, and hidden chambers

Nearly every royal tomb featured a remarkable architectural element known as the "well". Originally conceived as flood protection, these shafts acquired profound symbolic meaning within Egyptian magical traditions. Late Twentieth Dynasty tombs occasionally eliminated actual well excavation while retaining its symbolic representation within the overall design. Burial chambers typically occupied positions exceeding 200 meters beneath ground level, interconnected through elaborate networks of corridors and antechambers.

Changes from 18th to 20th Dynasty designs

Architectural development across dynasties followed clear evolutionary patterns. Early Eighteenth Dynasty constructions featured compact dimensions with narrow passages and oval-shaped burial chambers. Corridor slopes decreased progressively through successive designs, becoming virtually absent within late Twentieth Dynasty tombs. Later Ramesside constructions expanded dramatically, incorporating significantly wider passages and corridors. Queen Hatshepsut's tomb achieves record dimensions, descending 320 feet into solid rock across nearly 700 feet of total length.

The role of Deir el-Medina workers

Skilled artisans responsible for these elaborate constructions inhabited Deir el-Medina, a purpose-built village serving the valley's workforce. This specialized community, founded during Thutmose I's reign, accommodated approximately sixty-eight households at maximum capacity. Workers operated within two organized groups—left and right gangs—laboring on opposite tomb wall sections under foreman supervision. These middle-class craftsmen enjoyed exceptional benefits, including eight-day work cycles followed by two-day rest periods.

The Valley of the Kings houses an impressive 65 known tombs and chambers. These vary in complexity and scale, with some stretching hundreds of feet underground. The site continues to yield new discoveries, with the 63rd tomb (KV63) found as recently as 2006.

Customize Your Dream Vacation!

Get in touch with our local experts for an unforgettable journey.

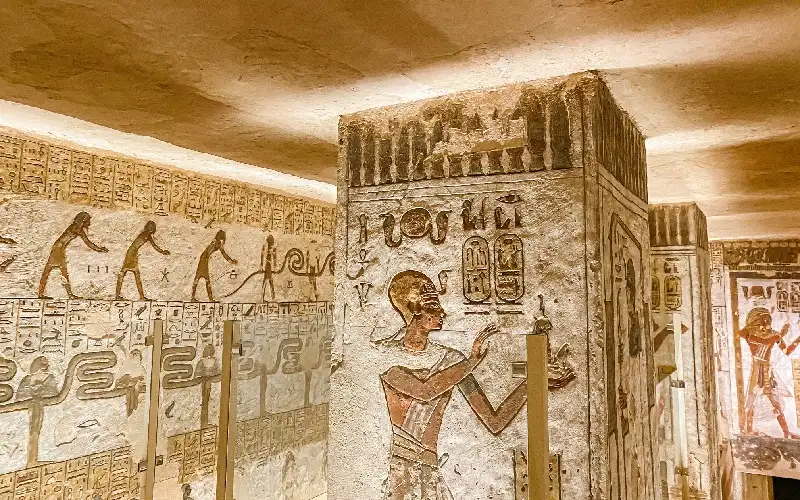

Plan Your TripReligious Symbolism and Tomb Decoration

Sacred artistry adorns tomb walls throughout the valley, each image serving a crucial spiritual purpose beyond mere decoration. These intricate paintings functioned as magical instruments, designed to ensure the pharaoh's successful passage through the perilous afterlife journey.

The Book of the Dead and other funerary texts

Ancient scribes developed the Book of the Dead from earlier Pyramid and Coffin Texts, creating a collection of protective spells for the deceased ruler's underworld voyage. Tomb walls also displayed various "Underworld Books" that mapped the sun god's nocturnal journey.

Starting with Horemheb's reign, the Book of Gates appeared on burial chamber walls, depicting the solar deity's passage through twelve nighttime gates. The Book of Caverns later emerged in upper tomb sections, while Ramesses III's burial chamber introduced the Book of Earth, which divided the netherworld into four distinct regions.

Depictions of gods and the journey through the underworld

Wall paintings captured pivotal moments when the deceased pharaoh encountered divine beings, most notably Osiris, ruler of the afterlife realm. These sacred scenes mapped the king's twelve-hour nocturnal voyage, showing his encounters with fearsome gatekeepers and supernatural beings bearing animal heads.

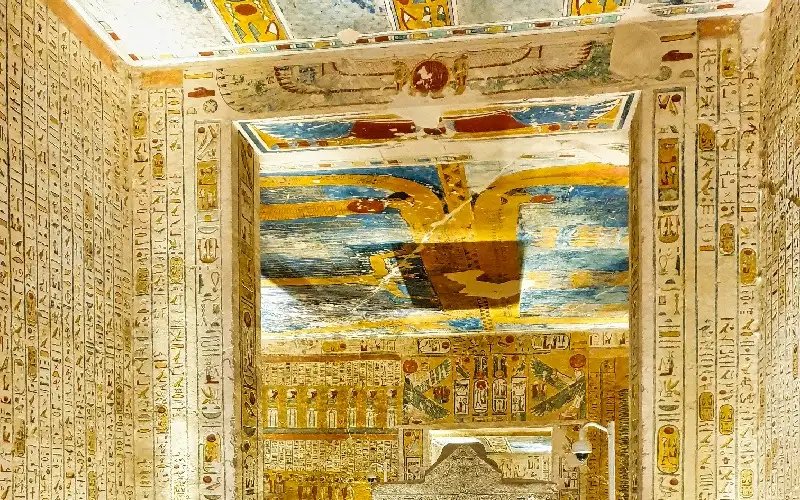

Ceiling art and astronomical themes

Burial chamber ceilings, particularly from Seti I's era onward, displayed the structured Book of the Heavens. These celestial masterpieces portrayed star-filled skies against deep blue backgrounds, creating a cosmic map that linked earthly existence with divine realms.

Use of color and symbolism in wall paintings

Ancient artists employed a sophisticated color language where each hue conveyed specific spiritual meanings: black evoked fertility and rebirth; white symbolized purity; red expressed both life force and peril; green indicated renewal; blue offered divine protection; and gold embodied eternal divinity.

Pharaohs chose hidden, underground tombs to protect their burials from tomb robbers and to symbolize the journey into the afterlife, aligning with ancient Egyptian religious beliefs.

Tomb Robbery, Rediscovery, and Modern Excavations

Elaborate security measures proved insufficient against the persistent threat of systematic tomb robbery that haunted the valley throughout ancient Egyptian history.

Ancient tomb robbers and their confessions

Court records from approximately 1110 BCE preserve startling confessions from ancient thieves. Amenpanufer, a mason, admitted his crimes with chilling detail: "We took our copper tools and forced a way into the pyramid of this king through its innermost part". These plunderers showed no reverence for royal remains—after stripping mummies of their precious valuables, robbers frequently "set fire to their coffins". Papyrus Mayer B documents another thief's confession about ransacking Ramesses VI's tomb, recording how the criminals methodically divided silver, bronze, copper, and linen among themselves.

The discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb

November 4, 1922, marked a pivotal moment when workers under Howard Carter's direction uncovered stone steps beneath shifting desert sand. Three weeks later, Carter carefully created "a tiny breach in the top left-hand corner" of the sealed doorway. His immortal response to the question of what he could see—"Yes, wonderful things!"—announced one of archaeology's greatest triumphs. The tomb yielded over 5,000 artifacts, requiring nearly a decade to properly catalog.

KV63 and other recent finds

Otto Schaden's team made headlines in 2005 with the discovery of KV63, the first unknown tomb located since Tutankhamun's find. This chamber contained no mummy but held sarcophagi, pottery, linens, and embalming materials. Archaeological experts theorize that "KV63 is an embalming cache; there must be a tomb to go with it".

Preservation efforts and archaeological challenges

Flash flooding continues to threaten the valley's structural integrity, creating ongoing preservation difficulties. Contemporary conservation efforts concentrate on tomb stabilization, environmental control systems, and carefully regulated visitor access.

The most renowned discovery in the Valley of the Kings is undoubtedly the tomb of Tutankhamun, found by Howard Carter in 1922. This tomb was remarkably well-preserved and contained over 5, 000 artifacts, providing an unprecedented glimpse into ancient Egyptian royal burial practices.

This ancient necropolis represents one of archaeology's most extraordinary repositories of human knowledge, illuminating the sophisticated world of pharaonic Egypt across five centuries of New Kingdom rule. The deliberate choice of location beneath al-Qurn's natural pyramid demonstrated remarkable foresight—royal architects achieved both symbolic resonance and practical security that earlier pyramid builders could never attain.

The story of systematic tomb robbery reveals the persistent human drama that unfolded here throughout antiquity. Court records preserve the very words of ancient thieves, creating an unexpected dialogue across millennia. Yet Tutankhamun's tomb escaped this fate through pure chance, offering modern visitors an intact glimpse into royal burial magnificence.

Each dynasty left its distinctive architectural signature within these limestone corridors. The evolution from bent-axis designs reflecting divine solar journeys to the grand straight-axis monuments of the Ramesside period illustrates how religious thought and engineering capability advanced together. Craftsmen from Deir el-Medina transformed these theological concepts into physical reality, carving sacred spaces deep within the desert bedrock.

Religious artistry served far more than decorative purpose throughout these burial chambers. Every painted scene, every carefully chosen pigment, every celestial map on tomb ceilings formed part of an elaborate spiritual technology designed to ensure royal resurrection. The Book of the Dead and its companion texts functioned as supernatural navigation systems for the perilous afterlife voyage.

Contemporary archaeological work continues revealing new dimensions of this ancient landscape. Otto Schaden's discovery of KV63 demonstrates that significant finds still await beneath the valley floor, while preservation specialists work to protect these irreplaceable monuments from environmental damage and visitor impact.

The Valley of the Kings endures as humanity's most vivid testament to ancient beliefs about death, divinity, and eternal life. Each tomb chamber functioned as a carefully engineered resurrection device, designed to transform earthly rulers into immortal gods through the power of art, architecture, and sacred knowledge.

A typical visit to the Valley of the Kings takes about two to three hours. This allows time to explore three to six tombs, depending on your pace and interest level. For a more in-depth experience, consider hiring a guide to provide historical context and insights.

The Valley of the Kings has a visitor center equipped with restrooms and a small-scale model of the entire valley to help plan your visit. There's also a tourist bazaar nearby where you can purchase snacks and cold drinks.

Yes, visitors must purchase an entry ticket, which typically allows access to three tombs. Certain tombs, such as Tutankhamun’s, require an additional ticket.

Photography is generally restricted inside the tombs. However, a separate photography pass may be available, though flash photography is strictly prohibited to protect the artwork.

Yes, but visitors should be prepared for uneven ground, steep stairways, and limited shade. Comfortable footwear and water are strongly recommended.